The Satrianum tower

- Dettagli

- Martedì, 06 Maggio 2014 16:00

![]() Versione italiana

Versione italiana ![]() Version française

Version française

General view of the excavation area with the cathedral, the episcopal seat, and the tower (from F. Sogliani, M. Osanna, L. Colangelo, A. Parente, “Gli spazi del potere...”, page 239)

The old city of Satrianum rose on the top of a hill, dominating some important routes toward the city of Potenza, the Vallo di Diano and the Agri Valley, overlooking both the castle of Brienza and the Picerno tower.

After the researches conducted during the 60’s by the British School at Rome, the site has been investigated by the Scuola di Specializzazione in Beni Archeologici of Matera from 2006 to 2009. At present,the archaelogical site is studied by the same Institute. The traces of the settlement of the Lucanian age (probably dating back to the fourth century B.C) were almost completely deleted by the medieval settlement, except for a little segment of the defention walls on the western side. Some blocks of the walls were reused for the costruction of the tower and they are clearly visible at the corners.

The first news of the existence of Satrianum date back to the early Middle Ages: in the agiography of Saint Laviero (1162- according to a transcription of 1562) the deacon of the church of the old city of Grumentum, Robertio di Romana, narrates about the transfer of the relics of the saint from Grumentum to Satrianum, because of the siege of the city by the Saracens (878 A.C.).

According to the the documentary sources, during the Norman domination the city was governed by a dominus (Sarlus at first and then Goffredo, between the late eleventh century and the early twelfth century) and it was also an important episcopal seat (dedication of an altar to Saint Stefano by the bishop Giovanni, whose notice dates back to 1080). The settlement of the city was enclosed by some walls and contained not only the dwellings, but also the two poles of the political and religious power: the square plan tower, which is decentralized if compared to the settlement, and the cathedral.

The tower, recently restored, is characterised by a tank on the groundfloor and it is structured on two levels, maybe with a third floor which has been lost. The entry is raised in relation to the road level to assure security against some possible enemy attacks. Presumably, it contained the accomodation of the lord, as well as some rooms which were functional to the life of the fort, as a treasury and a room for the storage of foodstaff.

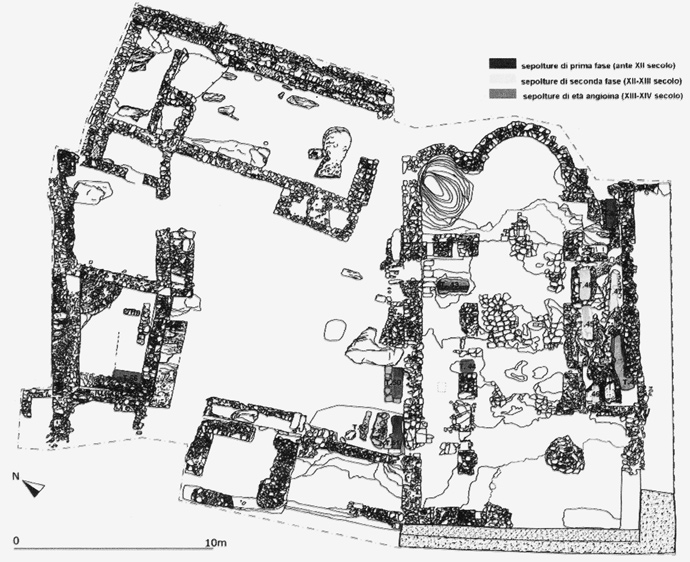

Plant of the cathedral and of the rooms of the episcopal seat with the position of the burials (from F. Sogliani, M. Osanna, L. Colangelo, A. Parente, "Gli spazi del potere", page 233)

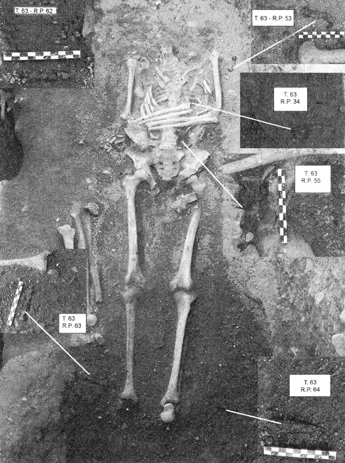

The cathedral has a three nave plant, of which the central is the largest one. All the three naves are asped, with two rows of squared pillars. The floor was partly constituted by terracotta tiles with some decorative patterns. During the Angevin age, the structure goes through many remakes: the terracotta tiles are substituted by stone sheets and the spaces of the lateral naves are divided. Inside the building and along the outside of the north wall, there are some privileged burials. For exemple, at the end of the left nave, a tomb in masonry (twelfth century) has been found. The tomb has four entombments: the oldest one, a woman, owed a rich dowry made of some metal ornaments, including twenty-four bronze little flowers belonging to a headgear. In addition, immediately to the left of the entry of the Cathedral there is another tomb in masonry (thirteenth-fourtheenth century) containing the remains of an high-ranking personality, whose skeleton kept still intact the corners of a linen or silk clothing.

A compound between the cathedral and the tower, composed by more rooms, and relevant to the episcopius, has been studied. These were the places where the religious community gathered, including also the service rooms. These settings are located around to an open space containing a big tank for water collection.

The cathedral and the episcopius were not the only religious buildings of the old medieval city: it is known that there was a monastry dedicated to Saint Blaise out of the Satrianum walls, and that there should be also a church dedicated to the Holy Mary inside the settlement. However, it is not certain where the two structures were placed.

One of the burials founded during the excavation (from F. Melia, "Il complesso architettonico", page 279)

The abandonement of the city should be cronologically dated during the fifteenth century, probably after a devastating earthquake. The site continued to be sporadically dwelled until the eighteenth century, when the stuctures fell definitively down.

According to a legend, the queen Joanna II of Naples (daughter of Charles II and Margaret of Durazzo, and that should not be confused with Joanna the Mad, daughter of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabela I of Castilia) took the decision of punishing Satrianum. She ordered to set fire to the city and to destroy it tragically. In this way, the queen would have revenged an offence suffered by one of her damsels carried out by some men of the place, during a stay in the city.

At present there are not any archaeological traces able to prove the fire of the city of Satrianum.

View of the inside of the tower before the recent restoration (from A. D'Ulizia, F. Sogliani, "Dai documenti d'archivio", page 177)

Italian bibliography

G. Spera, L’antica Satriano in Lucania, Cava dei Tirreni 1886.

D. Whitehouse, “Excavations at Satriano a deserted medieval settlement in Basilicata”, in “Papers of the British School at Rome”, XXXVIII 1970, pp. 188-219.

N. Laurenzana, Tito. Storia, vicende, personaggi, usi e costumi, fede, Cassola 1989.

L. Colangelo, “Il complesso architettonico della cattedrale di Satrianum. I risultati delle nuove indagini”, in M. Osanna, B. Serio, I. Battiloro (a cura di), Progetti di archeologia in Basilicata. Banzi e Tito, “Siris”, suppl. II, Bari 2008, pp. 183-192;

A. D’Ulizia, F. Sogliani, “Dai documenti di archivio al dato archeologico: Satrianum e la sua forma urbana”, in M. Osanna, B. Serio, I. Battiloro (a cura di), Progetti di archeologia in Basilicata. Banzi e Tito, “Siris”, suppl. II, Bari 2008, pp. 171-181.

M. Osanna, B. Serio, I. Battiloro (a cura di), Progetti di archeologia in Basilicata. Banzi e Tito, “Siris”, suppl. II, Bari 2008.

C. Albanesi, “Il complesso architettonico della Cattedrale di Satrianum. I risultati delle nuove indagini nell’area dell’episcopio”, M. Osanna, L. Colangelo, G. Carollo, Lo spazio del potere. La residenza ad abside, l’anaktoron, l’episcopio a Torre di Satriano, Venosa 2009, pp. 263-271.

F. Melia, “Il complesso architettonico della Cattedrale di Satrianum. Le sepolture”, in M. Osanna, L. Colangelo, G. Carollo, Lo spazio del potere. La residenza ad abside, l’anaktoron, l’episcopio a Torre di Satriano, Venosa 2009, pp. 273-280.

M. Osanna, L. Colangelo, G. Carollo, Lo spazio del potere. La residenza ad abside, l’anaktoron, l’episcopio a Torre di Satriano, Venosa 2009.

F. Sogliani, M. Osanna, L. Colangelo, A. Parente, “Gli spazi del potere civile e religioso dell'insediamento fortificato di Torre di Satriano in età angioina”, in P. Peduto, A.M. Santoro (a cura di), Archeologia dei castelli nell’Europa angioina (secoli XIII-XV), Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Salerno novembre 2008), Firenze 2011, pp. 227-241.